Patients often ask what’s more important: exercise or losing weight?

As winter rolls through the Northern Hemisphere, maintaining fitness seems a timely and relevant topic.

Heck, maintaining or gaining fitness should always be a relevant matter!

A recently published study seems worth a comment on Cycling Wednesday.

In this math-heavy publication in the journal, Circulation, researchers from South Carolina, shed light on the importance of maintaining, gaining or losing fitness over time.

The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study followed 14,435 men over 11 years. Researchers looked at how changes in fitness (measured by 2 treadmill exercise tests) and body weight (measured by BMI–Body Mass Index) related to death rates. Math people would say they focused on the delta—the change over time. (I added that sentence because I have fond memories of Calculus, and of course, I like to sound smart. < Insert > Grin.)

Here is a sifting down of the five major findings: (Again, good summaries–by professionals–can be found at CardioBrief and TheHeart.org.)

Men who maintained fitness reduced their death rate by 30%

Men who gained fitness reduced their death rate by 39%

Conversely, men who lost fitness doubled their risk of dying from heart disease.

For every 1 MET improvement in fitness (about 20 seconds/mile pace), there was a 15% reduction in death rate.

After adjusting for other causes, including changes in fitness, BMI by itself did not influence the risk of death.

This study reinforces my view that fitness remains central to health. The main contribution of this large and robust study stems from the novel finding that improving and maintaining fitness over time lowers mortality risk, while losing fitness worsens risk.

What’s up with the BMI data?

How could body weight not be significant?

The lack of effect of changes in weight are confusing. Some have interpreted the study as consoling to those who don’t lose weight but gain fitness. I have even read some headlines that suggest reducing fatness doesn’t reduce heart disease risk. That’s not what I think the study shows.

Rather, it showed that when BMI was looked at alone, excluding fitness, there wasn’t a significant increase in risk. That’s because most who gain fitness lose weight.

Also important is that this study looked at a specific and narrow population: men that were either normal weight or only slightly overweight (the average BMI was 26—thin by KY standards). Those individuals at normal body weight may not lose much weight when they begin an exercise program. Muscle mass increases can counter fat loss.

As pointed out by the researchers, it’s likely that losing weight would lower risk far more for those who are truly obese. My gut tells me that going from a BMI of 35 to 30 (14% less) would reduce risk more than going from 26 to 22.5. But what’s cool about the study findings is that normal weight people can markedly decrease heart disease risk by holding onto or gaining fitness.

So yes, I see this study as good news for the seemingly healthy patient who asks, “Doc, what else can I do to reduce my risk of dying?” Get fit, or fitter!

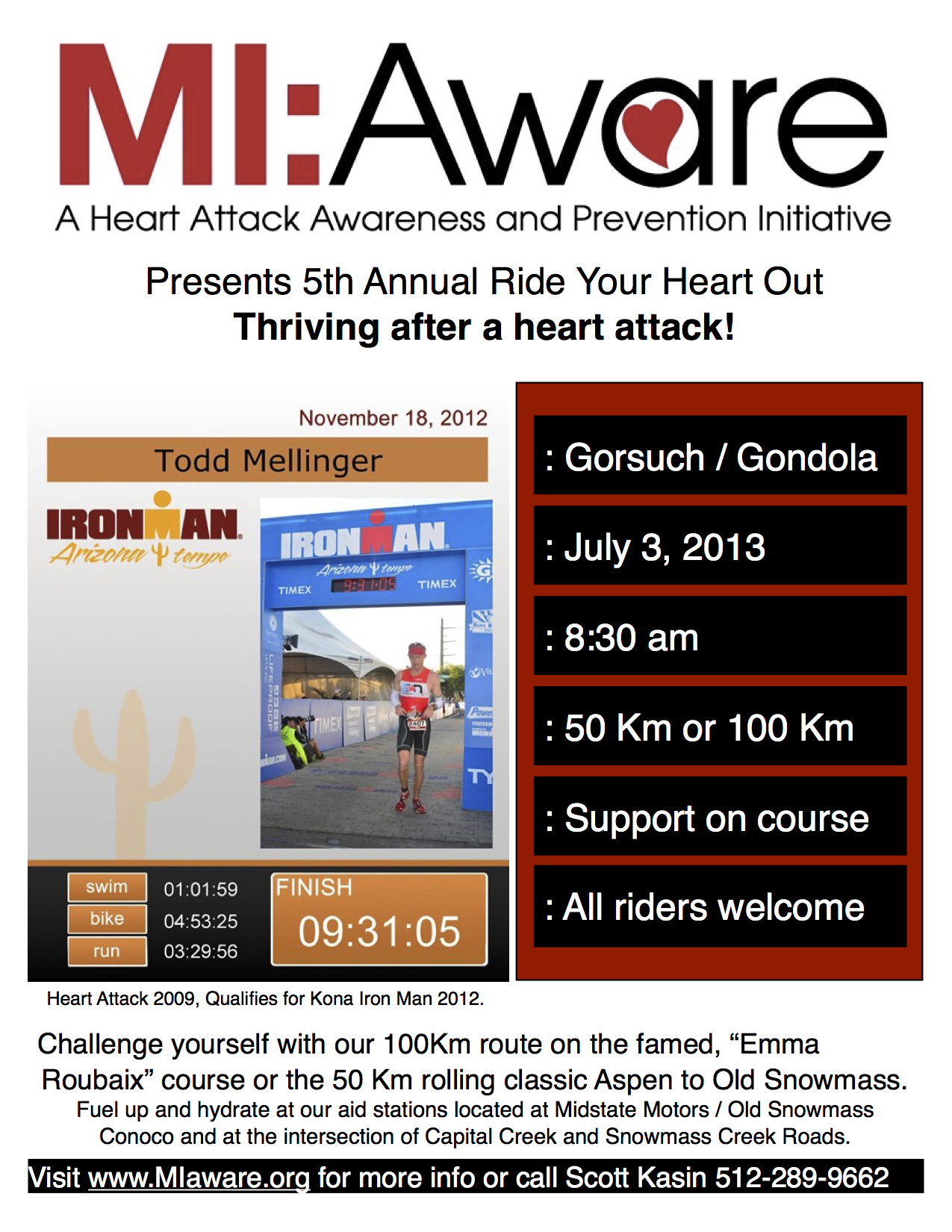

I also see it as a warning to competitive athletes to maintain fitness during the non-racing season. (Though not a coach, the thought of doing a different exercise in the off-season poofs into my mind here.)

The bottom line: fitness remains an incredibly powerful predictor of health. And fitness can be measured easily, without expensive scans or exposure to radiation.

For simple minds and minimalists, such news is reassuring.

JMM